Blog

5 most recent items

Here's all of the data I've accumulated so far, including my carbon footprint for 2024 (i.e. the year to now). This data covers both Joanna and me, so for two people. It's not exactly household data because between 2019 and 2022 we were actually working in different countries, so were technically two households. But since then we've both been living under one roof again.

| Source (CO2 tonnes) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 1.14 | 1.66 | 1.37 |

| Natural gas | 1.18 | 1.26 | 1.66 | 0.81 | -0.25 | 0.02 |

| Flights | 5.76 | 2.26 | 1.90 | 5.34 | 1.32 | 0.00 |

| Car | 1.45 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.12 |

| Bus | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.22 |

| National rail | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.47 |

| International rail | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Coach | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Taxi | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Food and drink | 1.69 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.35 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Clothing | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Paper-based products | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| Computer usage | 1.30 | 1.48 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Electrical | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Non-fuel car | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Manufactured goods | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Hotels, restaurants | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.21 | 1.21 |

| Telecoms | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Finance | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Insurance | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Education | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Recreation | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Total | 14.47 | 8.50 | 7.73 | 11.65 | 9.25 | 7.73 |

What can we say about these numbers? The headline result is that this year is joint-lowest on record at 7.73 tonnes of CO2. Lower is better, so this is a result I'm happy about. The other similarly low year was 2021, but that was slap bang in the middle of the pandemic, so rather a special case.

This year has been a relatively "normal" year, for some understanding of normal. If you account for the pandemic, I'd argue there's a good trend in the numbers: a decline from the high of 14.47 tonnes of CO2 in 2019 to nearly half that amount this year.

To understand why, it helps to look at the numbers that have gone in to the calculation.

| Source | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 1 794 kWh | 1 427 kWh | 3 009 kWh | 4 101 kWh | 5 975 kWh | 4 947 kWh |

| Natural gas | 6 433 kWh | 6 869 kWh | 9 089 kWh | 4 439 kWh | -1 362 kWh | 136 kWh |

| Flights |

36 580 km 20 flights |

14 632 km 8 flights |

25 542 km 14 flights |

36 042 km 20 flights |

7 233 km 4 flights |

0 km 0 flights |

| Car | 11 910 km | 2 000 km | 3 219 km | 8 458 km | 8 369 km | 9 364 km |

| Bus | 1 930 km | 40 km | 168 km | 133 km | 3 080 km | 2 065 km |

| National rail | 5 630 km | 400 km | 676 km | 0 km | 19 638 km | 13 184 km |

| International rail | 64 km | 1 368 km | 513 km | 8 684 km | 2 322 km | 1 914 km |

| Coach | 0 km | 0 km | 0 km | 0 km | 0 km | 1 200 km |

| Taxi | 64 km | 37 km | 100 km | 100 km | 100 km | 100 km |

| Tube | 0 km | 0 km | 0 km | 0 km | 100 km | 100 km |

As you can see, the biggest behavioural change has been a reduction in flying. This is partly — but not entirely — due to a change in circumstances. While living in Finland I was never able to find a practical alternative to flying between there and the UK (the shortest ferry and train alternative was a three-day trip). Now I'm in the UK I'm no longer making this regular journey. On top of that one of my 2024 new year's resolutions was to make twelve ecological improvements to my life. Avoiding flights was one of those and thankfully Joanna has been incredibly supportive in making this happen.

Despite this restrictions we did get to travel on holiday in 2024, but strictly by train and ferry. Avoiding flights did also impact my work plans and I'm grateful to my colleagues for also being supportive. I'm glad I was able to stick to this and the results are, I think, clear.

That's not the only story in these numbers. You can also now start to see the impact that switching from gas central heating to an air-source heat pump in 2022 has made. Natural gas usage has dropped right down (we still have a gas cooker, but I'm hoping to change that). The combined power usage, measured in kWh, is substantially lower after the change, giving an indication of the improved efficiency.

As a side note, it may seem odd that gas usage in 2023 was negative. That's due to our energy company not predicting the change caused by the heat pump and having to give us a rebate on anticipated gas usage. It's not ideal for the numbers, but I couldn't think of a better way to deal with it.

Another thing that's become clear is how much impact the pandemic had on our energy use. The four flights I took in 2021 were completely offset by other carbon outputs when compared to last year, when I took no flights at all. The pandemic really did hit the world hard.

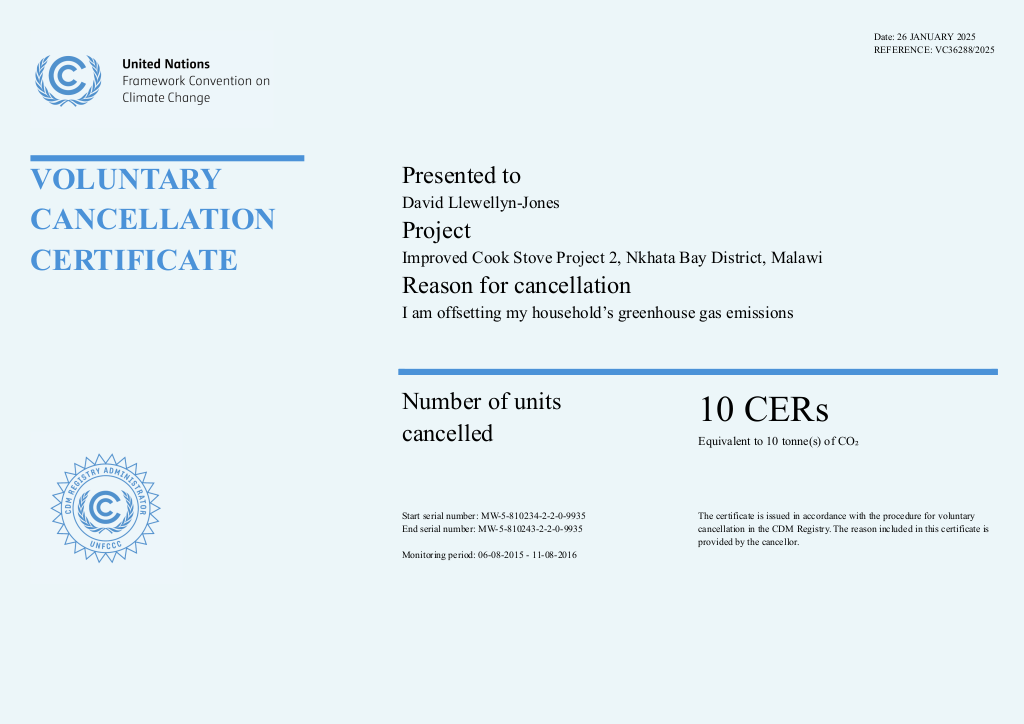

As always I've used these numbers to offset my carbon output for last year, using the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to support cooking stoves in Malawi. To be honest, I don't know whether this really makes a real difference to my climate impact, but it feels like a good cause either way.

More importantly, it's becoming clear that these annual audits have genuinely affected my behaviour, which in the longer term, may be the bigger win.

To generate the carbon output numbers above I used Carbon Footprint Ltd's carbon calculator. According to the same site, the average worldwide carbon footprint per person is about 4.79 tonnes. Taking into account the fact Joanna and I are two people, that now puts us below the average for the first time. It's a pretty clear conclusion, at least for our lifestyles: to really make a big difference, stop taking the plane.

This being the fifth instalment you know the drill and I'll try to keep things brief. So let's get straight to my list from 2024.

- Start working through "Information Theory: A Tutorial Introduction" by James V. Stone.

- Do something practical in Rust.

- Make twelve incremental ecological improvements to my life.

- Go to at least three events or exhibitions at the British Library.

Second we have my resolution to do something practical in Rust. I've continued attending and following the Rust reading group at work, but I admit that I've yet to find a practical outlet for the skills I've been learning. This falls entirely down to lack of motivation. If I really wanted to I could have found something, but the fact is it's much easier to work in a language I'm already proficient in. I don't plan to move it to my 2025 resolutions — there's no point in forcing it — but I'll keep it as a general goal. Doing this would offer real personal benefit.

Third is my desire to make twelve incremental ecological improvements to my life. The idea was to try to find roughly one per month. In practice and, somewhat to my surprise, I came within touching distance of achieving this. Many of the improvements were small, but that was the point: continual small improvements that could accumulate to become bigger aggregate improvements over time. I tried to keep track through the year:

- I planted our family Christmas tree from last year and miraculously it's still apparently healthy in the garden twelve months on.

- Joanna and I looked seriously into buying a new car, but decided that it would be better to keep our existing, 15 year old, car instead.

- I avoided using the dishwasher for 12 months. I've replaced it with washing up by hand, being careful to keep water usage low enough to be more efficient than the dishwasher would be.

- When I take a shower I now intentionally reduce the heat. Previously I always showered with the maximum, now I reduce it by quarter of a turn. It's a small win, but has the potential to be improved on in 2025 with an extra turn of the tap.

- At the recommendation of a friend at work I'm now buying only certified shade grown coffee. Apparently this is much better for the environment.

- This year I made special effort never to travel by plane. Given my previous years' failings I have plenty to make up for here. But I succeeded in making zero flights this year.

- When choosing my new home server, low power usage was a primary requirement. The device I ended up with is fanless and averages around just 12 Watts.

- I've also made a special effort to travel by train. Joanna will attest to this, as she's been very supportive when travelling together.

- Between June and August I cycled to Cambridge and back for my work commute seven times out of a possible 13. So there's room for improvement, but still better than the five I managed in 2023.

- Last January I offset my carbon output from 2023 with 10 Certified Emission Reductions.

Finally, I committed to going to at least three events at the British Library. In this I succeeded, visiting the Fantasy: Realms of Imagination, Beyond the Baseline: 500 Years of Black British Music and Medieval Women: In Their Own Words exhibitions. Honestly, all three were fantastic; better even than I'd expected. So I'm glad I committed to this.

In total then for 2024 it's 2.83 out of four: a pretty good result in my world. So what's in store for 2025?

Here are my planned resolutions for the year ahead:

- Prioritise Codeberg over GitHub.

- Do something fun outside the house at least once per week.

- Read at least one paper per week.

Given all this, I'd love to move off GitHub for my personal projects. The obvious alternative right now seems to be Codeberg given its strong open-source and community credentials. So I'd really like to resolve to move all my projects there. Unfortunately moving existing projects to a different platform can be destructive (for example with loss of issues and open pull requests). I'm therefore resolving to start all new open source projects on either Codeberg or my self-hosted git server. I should also start moving existing projects, but that'll have to be on a best-effort basis.

Next up I'm resolving to do something recreational outside the house at least once per week. This might sound strange to a normal person, but I spend so much time inside and online that I can easily go an entire week without doing something recreational in the real world. Of course, I often leave the house for work, shopping or other non-recreational activities. But the plan here is to do something fun. It could be going to the cinema, visiting friends or just going for a walk in the local countryside. But it should be something. I've run this past Joanna and she's on board with this: it'll be a combined effort.

Finally I plan to read at last one research paper each week. This is an idea I stole from Dr Esther Plomp, a researcher I know through her contributions to The Turing Way. Dr Plomp committed to reading one paper a day but I've diluted this to one per week to suit my own lower standards. I'm also keeping my definition of a "research paper" pretty loose. If I end up reading a book chapter instead, that's fine.

So those are my three resolutions. I thought about including several others, but I think it's important to stay focused. Here are a few that didn't make the cut:

- Complete "Information Theory: A Tutorial Introduction" by James V. Stone.

- Complete all the exercises in Linear Algebra Done Right by Sheldon Axler.

- Add Cambridge live bus info to an app.

With my home server back up and running I feel in good shape for the year to come. So, roll on 2025! See you in twelve months with the results in Part VI.

This particular device is the snappily named "12th Gen Intel Firewall Mini PC Alder Lake i3 N305 8 Core Fanless Soft Router Proxmox DDR5 4800MHz 4xi226-V 2.5G". It seems to be available under a range of different brand names, but I believe CWWK is the manufacturer.

I've spent the last three or four days configuring the hardware and software on it so that it's just as I want it. Here are the main things I've configured on it and which I plan to make most use of:

- SSH

- Apache 2

- Let's Encrypt

- Nextcloud

- File sharing

- Shared calendar

- Contact sharing

- Phone backup

- Gitolite

- Subversion

- Jitsi

- OpenVPN

- ZNC

- BIND

- Offsite backups

- Various Cron jobs

But before I talk about my experiences with the device itself, first let me say something about its delivery. I ordered the device direct from CWWK on 2nd December. Between then and the 17th December I heard nothing from them, which gave me considerable pause for thought and made me rather nervous.

The website looks legitimate at first, but the more you look at it the more dubious it looks. Support is provided through a GMail address and the shop still shows Shopify branding (the Social media links point to Shopify defaults). While the support questions I asked before ordering were answered swiftly, following my purchase my questions went unanswered. If you search the web there are several automated reports of the cwwk.net site being bogus. On the other hand you'll also find forum posts claiming that everything went fine when ordering from them.

I'd resigned myself to the server never arriving and me losing my money when on 17th December I received an alert claiming a package was heading my way, along with a tracking link. The package eventually arrived from China ten days later with server and everything else enclosed, intact, working and just as expected. So, apparently not a scam after all!

Nail-biting period of angst aside, CWWK fully delivered my order and I don't regret that I bought it direct from them. But I'm just a random person on the Internet, so if you're thinking of doing the same please don't take this as being any sort of evidence!

The best way to describe the hardware itself is solid. Heavy and solid. It looks a bit like a standard metal-encased mini PC, but sporting a wild haircut. That's because this thing needs a big-ol' heat-sink to dissipate excess energy during periods of heavy use.

It's also bristling with ports: four 2.5 G Ethernet ports, eight USB-A ports, HDMI, DisplayPort, a micro SD Card reader and power in. There are no USB-C ports.

Some notes about this configuration: there are other very similar devices available that have USB-C ports. If I planned to use this as a desktop replacement I'd absolutely want USB-C ports. I'd want it powered over USB-C. I wouldn't want any USB-A ports at all.

But I plan to use this as a headless server, equivalent of a cloud device, so I expect to plug devices into it only very rarely. So for my purposes the lack of USB-C isn't a problem. But I'd very much expect others to feel differently about this.

Although it's great to have 2.5 G Ethernet, in practice I can't really make use of the full bandwidth on my home network. The Intel i226-V network controllers that provide the 2.5 G support are too new to be picked up by anything except relatively new Linux kernels, which is something to be aware of.

For software, I'm running Ubuntu 24.04, which is the first LTS release to support the Ethernet ports. With this, everything is working just great.

From a performance point of view I've so far found it to be excellent. Desktop performance is completely usable, although that's not something I'm concerned about. More importantly for me I've found performance as a network server to be great. To be honest, my previous server had become noticeably slow at serving Nextcloud pages. That had an Intel Atom N2800 CPU with two cores, compared to the N305 in this device with eight cores. That's a big jump up so it's not really surprising it feels so swift.

Being fanless you can't hear any activity from it unless it's the dead of night and you stick your ear right up against it. But the chassis does give off some heat. While idle it stays mildly warm — not warm enough to be comfortable bath temperature — but during burst usage it gets a lot warmer. It's never hot though and placing my hand firmly on it has yet to feel uncomfortable.

I bought the device bare-bones for $327.40 including the expansion board that increases storage to five M.2 NVMe slots. I spent £141.34 on 16 GiB of SO-DIMM RAM, a 500 GB Gen4 NVMe SSD (4 700 MB/s) for the operating system and a 1 TB Gen4 SSD (5 150 MB/s) for data. So the complete package set me back £400.

My last device ran for 12 years before failing, so it's a bit early to rush to any judgement, but if this one last a couple of years I'll consider that to be money well spent. Right now, it's doing the job I bought it for perfectly and I'm very happy with it.

So I'm happy. But there's an obvious follow-up question to all of this: would I have been equally happy with the other devices I considered buying?

I made fans a deal-breaker during the decision-making process and I stand by this decision. This is my first server that's had no moving parts and I'm happy with the silence and reassurance this brings. When I entered the world of computing in the nineties moving parts were a rarity and it gratifies me that by the time I leave the world of computing we'll have returned to the same paradigm.

On the other hand, it's harder to justify my decision to go with an N305 processor when I suspect an N100 would have been more than sufficient and would probably have ended up more power-efficient as well. Eight cores sounds great, but in practice four probably would have been enough.

In particular, while the solid metal case of this CWWK device is one of its best features, if I'd dropped down to an N100 processor this may not have been necessary. In summary, with an N305 the metal case is probably wise, but less so for one of the more power-efficient CPUs.

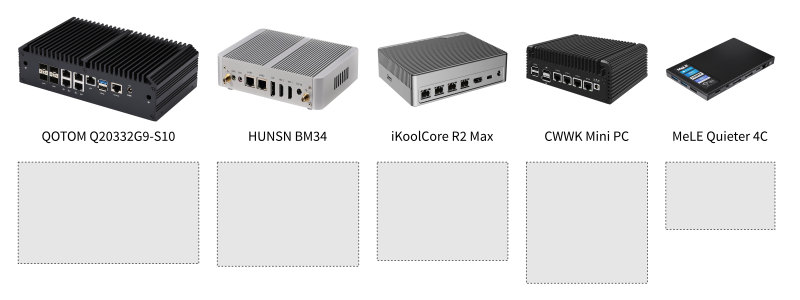

I have to conclude that many of the other devices would have worked just fine as well. Of the twelve I considered, it looks like the HUNSN BM34, iKoolCore R2 Max and Shuttle XPC slim DL30N would all have been just fine. Some of the others would have been fine were it not for the fact they had fans, came with Windows pre-installed, or lacked the space for two drives.

But clearly these are all rather personal to my requirements. It's easy to conclude that we live in a world of rich possibilities. There are numerous great options for low-power home servers and having one of these can offer a genuine quality of life improvement.

I call it a home server, but more recently the term Home Lab seems to have become more popular. I use it for running my personal cloud services, experimenting with various server technologies and helping me orchestrate my home network. Since I avoid corporate cloud services like Google and Dropbox it provides me with a pretty essential set of services.

Until recently it was running Nextcloud (shared drive, calendar, contacts, phone backup), Bind9 (DNS), git (development), SVN (development), Apache2 (Web server), OpenVPN (VPN), Jitsi (video conferencing), ZNC (IRC bouncer), an FTP server, SMB shares, media sharing, backup to AWS and various cron-jobs.

That looks like quite a lot, but in practice all of this can be run with very modest compute capabilities.

The first Constantia incarnation was a Koolu Net Appliance running an AMD Geode LX 800 processor that I bought for a couple of hundred pounds in November 2007.

It worked great for many years until Ubuntu dropped support for the Geode, which caused me a bit of trouble. It sadly died after about five years and I replaced it with an Aleutia T1 running a Celeron J1800 processor.

Both the Koolu and Aleutia were fanless and both ran great. Until a couple of months back when the Aleutia also died. At first I thought it might have been a hard drive failure, but on testing the components I found both the internal SSD and 2.5 inch HDD were working fine.

In truth it was getting a little slugging even for server tasks running the latest Ubuntu. So I've taken the hint that after seven years of trusted service, it's time to upgrade the hardware to a new device again.

As well as being fanless, both devices were also diminutive, the larger Aleutia measuring just 35 mm × 180 mm × 200 mm. Over the last decade or so there's been a positive explosion in the number and diversity of mini PCs on the market, driven in part by the success of the Raspberry Pi, but also in part by Intel's NUC initiative and no doubt a wealth of other factors.

This is great in terms of options, but also means a much harder time choosing. So I'm taking the same approach I've typically done when buying a new laptop, involving a table of specs, some rationale for ruling out certain options, and a final choice that's based largely on guesswork and impulse.

Given my experience with my previous servers, I know the following are going to be important to me:

- Small footprint: the Aleutia was already pushing the limits of acceptability (in terms of width and depth), so ideally no larger than this.

- Fanless: for the sake of my own sanity, no noise is key.

- Low idle power: it's going to be running 24/7 but will spend most of the time awaiting incoming network connections.

- Linux compatible: I'll be running Ubuntu on it; having to pay for a Windows or macOS licence would be irksome.

- Upgradable: 16 GiB RAM, 512 GiB storage at minimum with more in the future.

- Generic hardware: experience with the Geode tells me a generic chipset is preferable if it's going to be running for many years.

- Multi-core: the cores don't have to be fast, but at least four will be helpful for running as a Web server.

- Price: there's a limit to how expensive small PCs can get and given the cost will effectively be amortised over multiple years, I'm willing to pay for something worthwhile.

- GPU: some parallel compute would be nice, but I'm not planning to play any games.

- Miniscule: small is good, but I'd rather have the potential to add a spare HDD than have it smaller than my thumb.

- Multi-display: it'll be a headless Web server, so will only get connected to a display under exceptional circumstances.

- Glitz: flashing lights, glowing logos, embedded displays; they'll just be a waste.

With all this in mind I've been scouring the Web for mini PCs over the last month to try to find anything that might fit the bill. Right now, N100 and N305 devices seem to be top of the range for fanless mini PCs. There are also Ryzen processors that compete, but in practice, the requirement for the device to be fanless constrains things quite significantly.

Here's the table with the contenders. In the first block the first two columns show my previous devices for comparison. I've also included two devices with fans (the ASUS NUC 14 Pro and the Mac Mini M4), also just for comparison.

The second block show the five most likely contenders. Then the third block show five other systems I compared against, but all of which have flaws significant enough for me to reject them as options.

Colour coding:

| Good |

| Acceptable |

| Bad |

| Previous hardware |

|

Koolu |

Aleutia T1 |

Asus NUC 14 Pro |

Mac Mini M4 |

|

|

|

Company |

|

||||

|

Review |

|

||||

|

Height (mm) |

35.0 |

35.0 |

54.0 |

50.0 |

|

|

Width (mm) |

130.0 |

180.0 |

112.0 |

127.0 |

|

|

Depth (mm) |

140.0 |

200.0 |

117.0 |

127.0 |

|

|

Weight (kg) |

1.000 |

0.991 |

0.600 |

0.670 |

|

|

Fan |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Metal chasis |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

|

Power idle (W) |

5.00 |

10.00 |

8.00 |

6.00 |

|

|

Power load (W) |

5.00 |

10.00 |

88.00 |

40.00 |

|

|

Processor |

AMD Geode LX 800 |

Celeron J1800 |

Core Ultra 7 |

M4 |

|

|

Cores |

1 |

2 |

16 |

10 |

|

|

Memory (GiB) |

0.5 |

1.0 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

|

|

SSD bays |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

SSD (TiB) |

0.04 |

0.56 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

OS |

Ubuntu |

Ubuntu |

Windows 11 |

macOS |

|

|

Price (£) |

200 |

200 |

800 |

1000 |

|

|

Price inc. mem. (£) |

200 |

200 |

800 |

1000 |

|

|

Pros |

|

|

Processor |

Idle power; perfromance |

|

|

Cons |

|

|

Fan |

Fan |

|

|

Notes |

Bought 2007 |

Bought 2013 |

|

|

|

|

QOTOM Q20332G9-S10 |

HUNSN BM34 |

iKoolCore R2 Max |

CWWK Mini PC |

MeLE Quieter 4C |

|

|

Company |

|||||

|

Review |

|||||

|

Height (mm) |

62.0 |

50.0 |

40.0 |

53.6 |

18.3 |

|

Width (mm) |

122.0 |

125.0 |

118.0 |

145.4 |

81.0 |

|

Depth (mm) |

217.0 |

170.0 |

157.0 |

145.6 |

131.0 |

|

Weight (kg) |

2.500 |

1.500 |

1.050 |

1.800 |

0.203 |

|

Fan |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Metal chasis |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Power idle (W) |

16.00 |

6.00 |

10.00 |

9.00 |

7.10 |

|

Power load (W) |

32.00 |

10.00 |

24.00 |

36.00 |

18.50 |

|

Processor |

Atom C3758R |

N100 |

N100 |

N305 |

N100 |

|

Cores |

8 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

4 |

|

Memory (GiB) |

32.0 |

0.0 |

16.0 |

32.0 |

16.0 |

|

SSD bays |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

SSD (TiB) |

1.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

0.50 |

|

OS |

Linux |

Linux |

Linux |

Linux |

Linux |

|

Price (£) |

400 |

168 |

500 |

327 |

240 |

|

Price inc. mem. (£) |

400 |

268 |

500 |

327 |

240 |

|

Pros |

8 cores |

Good fit |

Good fit |

Great performance |

Small, low power |

|

Cons |

No acceleration |

|

Pre-order |

Gets hot |

Not upgradable |

|

Notes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MINIX Neo Z300-dB |

MINIX Z100-0db |

Asus NUC 13 rugged |

Shuttle XPC DL30N |

MeLE Quieter 3Q |

|

|

Company |

|||||

|

Review |

|||||

|

Height (mm) |

46.0 |

46.0 |

35.8 |

43.0 |

61.0 |

|

Width (mm) |

120.0 |

120.0 |

108.0 |

165.0 |

146.0 |

|

Depth (mm) |

123.0 |

123.0 |

174.0 |

190.0 |

200.0 |

|

Weight (kg) |

0.890 |

0.890 |

1.060 |

1.300 |

0.182 |

|

Fan |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Metal chasis |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Power idle (W) |

10.00 |

8.00 |

3.70 |

9.46 |

2.40 |

|

Power load (W) |

31.00 |

26.00 |

18.00 |

22.00 |

10.90 |

|

Processor |

N300 |

N100 |

N50 |

N100 |

N5105 |

|

Cores |

8 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

|

Memory (GiB) |

16.0 |

16.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

8.0 |

|

SSD bays |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

SSD (TiB) |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.25 |

|

OS |

Windows 11 Pro |

Windows 11 Pro |

Linux |

Ubuntu |

Windows 11 Pro |

|

Price (£) |

340 |

270 |

318 |

224 |

190 |

|

Price inc. mem. (£) |

340 |

270 |

418 |

324 |

190 |

|

Pros |

Good processor |

Good value |

Good fit |

Good fit |

Tiny |

|

Cons |

No SSD Bay |

No SSD Bay |

Slow processor |

Hard to source |

Poor specs |

|

Notes |

|

|

|

|

|

There are perhaps a few things worth noting in this table. This isn't intended to be a comprehensive comparison, it's just covering the issues that matter to me. For example, processor speed isn't included because I'm more concerned about the number of cores. I've also not included anything about connectivity (USB, HDMI and so on) because all of these systems reach the baseline for my needs.

As I mentioned above, my intention is to get a system with at least 16 GiB RAM and 1 TiB of solid state storage. Not all of the systems come with this specification, so alongside the price of the system I've also included a line showing the price after adding on the cost (which I estimate to be around £100) of any additional storage needed.

Almost all of the columns include at least one red ("bad") entry. The existence of a bad entry may not be enough to trigger an immediate rejection.

Let's go through each of the contenders and consider their benefits and drawbacks.

The QOTOM Q20332G9-S10 is arguably the most interesting of the options here. The processor is an older generation, with only very basic GPU acceleration, but with the ability to offload crypto, which could be a really useful feature for my needs. It also has eight cores which is also great for what I need. The main downside of it being older and with better networking is that it requires a fair bit more juice on idle than newer generations. This is the biggest downside of this device for me. Crucially, it seems this device is built as a server with 10 G networking, rather than a home PC. That's really what I'm looking for.

I'm particularly taken by the design of the HUNSN BM34 with its all-metal chassis and clean looks. It also claims to have space for a 2.5 inch drive inside. I'm not sure if I'll use this in the long run, but this is nice to have. It's incredibly good value with very low power requirements and the reviews on Amazon also shed it in a positive light. One downside is that I can only find minimal information about the BM34 model, which I couldn't even find listed on the HUNSN website. While it does have WiFi, it only has 1 G networking when I'd prefer 2.5 G at least.

The iKoolCore R2 Max fits many of my requirements. It's apparently really well made and the N100 model doesn't suffer from throttling under load. It's not super-fast, but likely good enough for my needs. The device is built in and shipped from Hong Kong and when I contacted the company about taxes I was pretty happy with how they responded. The company also offers comprehensive documentation, which is pretty unusual in this space from what I can tell. The biggest positive of this device is the 10 G networking. The biggest downside for me is the fact it's not supposed to be user-serviceable. There are flaps on the underside for access to RAM and storage slots, but iKoolCore have used hexagonal screws for the main chassis. I can understand why, but I've really appreciated being able to open up my Aleutia device, so this would be a retrograde step. There's also no space for a 2.5 inch drive and it's expensive compared to the other devices I'm considering.

I added the CWWK Mini PC device explicitly so that I could have an N305 powered device in the list. When I started this search it became clear pretty early on that the Intel N100 and N305 were the most likely candidates for a small fanless device. The N305 has twice the cores, but the extra power obviously pushes the thermal envelope for a fanless design and I didn't find many that support it. This CWWK device looked like the most promising for running an N305. The idle power is still low and while the burst power is high, that's not such an issue for me. More of an issue is the fact there's no room inside for a 2.5 inch drive, which is a shame. On the plus side, 2.5 G networking is nice and there's an expansion board offering support for up to four SSDs. Neat.

The MeLE Fanless Quieter 4C is the smallest of the devices I looked at. And it really is very small. There's certainly something exciting about having a proper server that's barely larger than a Raspberry Pi. Unfortunately there are some compromises that come with this. In particular, the memory and storage are soldered on, so can't be upgraded. It can be bought with up to 32 GiB RAM and 512 GiB eMMC storage, plus the option to add an SSD, so this would still be workable. The case is also plastic rather than metal, which makes me a bit concerned about thermal dissipation. This would make a great mini-PC for desktop use, but I'm not so convinced it'd make a great home server.

There seems to be a lot to commend all of these devices. Ultimately I've decided to go with the CWWK Mini PC N305 device. I'm calling it that because its proper title appears to be "12th Gen Intel Firewall Mini PC Alder Lake i3 N305 8 Core Fanless Soft Router Proxmox DDR5 4800MHz 4xi226-V 2.5G"; not a name anyone wants to have to repeat. I'll go for the Intel i3-N305, bare bones model with NVME expansion interface to support four drives (I plan to use two, which I'll source separately). My aim will be to transfer over the data from Constantia to it to create a Constantia Mk III. I'll share the results here when I do.

Indeed, for many years WebKit was also an integral part of Sailfish OS, providing the embeddable QtWebKit widget that many other apps used as a way of rendering Web content. It wasn't until Sailfish OS 4.2.0 that this was officially replaced by the Gecko-based WebView API.

The coexistence of multiple engines within the operating system isn't the only reason many people felt WebKit would make a better alternative to Gecko. Another is the fact that WebKit, and subsequently Blink, has become the defacto standard for embedded applications. In contrast, although Mozilla were pushing embedded support back when Maemo was being developed, it's since dropped official embedded support entirely.

So in this post I'm going to take a look at embedded browsers. What does it mean for a browser to be embedded, what APIs are supported by the most widely used embedded toolkits, and might it be true that Sailfish OS would be better off using Blink? In fact, I'll be leaving this last question for a future post, but my hope is that the discussion in this post will serve as useful groundwork.

Let's start by figuring out what an embedded browser actually is. In my mind there are two main definitions, each embracing a slightly different set of characteristics.

- A browser that runs on an embedded device.

- A browser that can be embedded in another application.

If you frame it right though, these two definitions can feel similar. Here's how the Web Platform for Embedded team describe it:

In contrast, an embedded browser is contained within another application or is built for a specific purpose and runs in an embedded system, and the application controlling the embedded browser does not provide all the typical features of browsers running in desktops.

So minimal, encapsulated, targeted. Maybe something you don't even realise is a browser.

And what does this mean in practice? That might be a little hard to pin down, but for me it's all about the API. What API does the browser expose for use by other applications and systems? If it provides bare-bones render output, but with enough hooks to build a complete browser on top of (at a minimum) then you've got yourself an effective embedded browser.

In the past Gecko provided exactly this in the form of the EmbedLIte API and the XULRunner Development Kit. The former provides a set of APIs that allow Gecko to be embedded in other applications. The latter allows the Gecko build process to be harnessed in order to output all of the libraries and artefacts needed (such as the libxul.so library and the omni.ja resource archive) to integrate Gecko into another application.

Sadly Mozilla dropped support for both of these back in 2016, when it was decided the core Firefox browser needed to be prioritised over an embedding offering. Mozilla has made plenty of questionable decisions over the years and given the rise in use of WebKit and Chrome as embedded browsers, you might think this was one of them. But despite the lack of investment in the API, it's not been removed entirely, to Mozilla's credit. It is, in fact, still possible to access the EmbedLite APIs and to generate the XULRunner artefacts and get a very effective embedded browser.

We'll come back to the EmbedLite approach to embedding later. But in order to understand it better, I believe it's also helpful to understand the context. I therefore plan to look at three different embedded browser frameworks. These are CEF (the Chromium Embedded Framework), Qt WebEngine and then finally we'll return to Gecko by considering the Gecko WebView.

Looking through the documentation I was surprised at how similar these three frameworks appear to be. But trying them out I was quickly divested of this misapprehension. They do offer similar functionality, but turn out to be quite different to use in practice.

Before we get in to the API details, let's first consider what a minimal embedded browser external interface might look like.

- Settings controller. An API, likely exposed as a class, to control browser settings such as cache and profile location, scaling, user agent string, privacy settings and so on. Browsers typically offer numerous configuration options and some of these such as profile location are especially important for the embedded case.

- JavaScript execution. Apps that embed a browser often have particular use-cases in mind. The ability to execute JavaScript is important for allowing interaction between the rendered Web content and the rest of the application (see also message passing interface).

- Web controls. There are a bunch of controls that are needed as a bare minimum for controlling browser content. Load URL; navigate forwards; navigate backwards; that kind of thing. An app that embeds a browser may choose to handle these controls itself, potentially hiding them from the user entirely, but at the very least the app has to be able to access these controls programmatically from its own code.

- Separate view widgets. The browser is an engine and often an app will want multiple views all of which make use of it, each rendering different content. An embedding framework should allow an app to embed multiple views, each making use of the same engine underneath.

- Message passing interface. The app and the browser need a way to communicate with one another. Browsers already work by broadcasting messages between different components, so there should be a way for the embedder to send and receive these messages as well. A common use case will involve the embedder injecting some JavaScript, with communication handled by message passing between the app and the JavaScript. The app can then act on the messages sent from inside the browser engine by the JavaScript.

- Populate a settings structure for the browser to capture the settings in an object.

- Instantiate a bunch of singleton browser classes. These will be for central management of the browser components.

- Pass in the settings object to these central browser components.

- Embed one or more browser widget into the user interface to create browser views.

- Inject some JavaScript into the browser views. This JavaScript listens for messages from the app, interacts with the browser content and sends messages back.

- Open the window containing the browser widget for the user.

- Interact with the JavaScript and browser engine by passing messages via the message passing interface.

- When the user closes the window, shut down the views.

Let's now turn to the three individual embedding frameworks to see how they approach all this.

CEF

Let's start by considering the CEF API as documented. I actually began by looking at the Blink source code, but it turns out this isn't set up well for easy integration into other projects. I should caveat this: the underlying structure may be carefully arranged to support it, but the Blink project itself doesn't seem to prioritise streamlining the process of embedding. For example it exposes the entire internal API with no simplified embedding wrapper and I didn't find good official documentation on the topic.And that's exactly how CEF brings value. It takes the Chromium internals (Blink, V8, etc.) and wraps them with the basic windowing scaffolding needed to get a browser working across multiple platforms (Linux, Windows, macOS). It then adds in a streamlined interface for controlling the most important features needed for embedding (settings, browser controls, JavaScript injection, message passing).

Having worked through the documentation and tutorials, the CEF project assumes a slightly different workflow from what I'd typically expect. Qt WebEngine and Gecko WebView are both provided as widgets that integrate with the graphical user interface (GUI) toolkit (which in these cases is Qt). On the other hand, CEF is intended for use with multiple different widget toolkits (Gtk, Qt, etc.). As a developer you're supposed to clone the cef-project repository with the CEF example code — which is complex and extensive — and build your application on top of that. As is explained in the documentation, the first thing a developer needs to do is to:

The documentation assumes you're starting from scratch; it's not clear to me how you're supposed to proceed if you want to retrofit CEF into an existing application. It looks like it may not be straightforward.

Nevertheless, assuming you're starting from scratch, CEF provides a solid base to build on, since you'll start with an application that already builds, runs and displays Web content. You can then immediately see how the main classes needed for controlling the browser are used.

There are many such classes, but I've picked out three that I think are especially important for understanding what's going on. As soon as you look into one of these classes you'll find references to other classes. You may need to look into these too if you want to fully understand what's going on; with each such step I found myself getting pulled a little further into the rabbit hole.

First the CefBrowserHost class. This class is pretty key as it handles the lifespan of the browser; it's described in the source as being "used to represent the browser process aspects of a browser". Here's a flavour of what the class looks like. I've cut a lot out for the sake of brevity, but you can check out the class header if you want to see everything.

class CefBrowserHost : public CefBaseRefCounted {

public:

static bool CreateBrowser(const CefWindowInfo& windowInfo,

CefRefPtr<CefClient> client,

const CefString& url,

const CefBrowserSettings& settings,

CefRefPtr<CefDictionaryValue> extra_info,

CefRefPtr<CefRequestContext> request_context);

CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> GetBrowser();

void CloseBrowser(bool force_close);

[...]

void StartDownload(const CefString& url);

void PrintToPDF(const CefString& path,

const CefPdfPrintSettings& settings,

CefRefPtr<CefPdfPrintCallback> callback);

void Find(const CefString& searchText,

bool forward,

bool matchCase,

bool findNext);

void StopFinding(bool clearSelection);

bool IsFullscreen();

void ExitFullscreen(bool will_cause_resize);

[...]

};

As a developer you call CreateBrowser() to start up your browser, which you can then access using GetBrowser(). Once you're done you can destroy it using CloseBrowser(). All of these are accessed via this CefBrowserHost interface. As you can see, there are also a bunch of browser-wide functionalities (search, fullscreen mode, printing, etc.) that are also managed through CefBrowserHost.Here's the interface for the CefBrowser object the lifecycle of which is being managed (you'll find the full class header in the same file):

class CefBrowser : public CefBaseRefCounted {

public:

bool CanGoBack();

void GoBack();

bool CanGoForward();

void GoForward();

bool IsLoading();

void Reload();

void StopLoad();

bool HasDocument();

CefRefPtr<CefFrame> GetMainFrame();

[...]

};

Things are starting to look a lot more familiar now, with methods to perform Web navigation and the like. Notice however that we still haven't reached the interface for loading a specific URL yet. For that we need a CefFrame which the source code describes as being "used to represent a frame in the browser window.". A page can be made up of multiple such frames, but there's always a root frame which we can extract from the browser using the GetMainFrame() method you see above.Once we have this root CefFrame object we can then ask for a particular page to be loaded into the frame using the LoadURL() method:

class CefFrame : public CefBaseRefCounted {

public:

CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> GetBrowser();

void LoadURL(const CefString& url);

CefString GetURL();

CefString GetName();

void Cut();

void Copy();

void Paste();

void ExecuteJavaScript(const CefString& code,

const CefString& script_url,

int start_line);

void SendProcessMessage(CefProcessId target_process,

CefRefPtr<CefProcessMessage> message);

[...]

};

The full definition of CefFrame can be seen in the cef_frame.h header file.So now we've seen enough of the API to initialise things and to then load up a particular URL into a particular view. But CefFrame offers us a lot more than just that. In particular it offers up two other pieces of functionality critical for embedded browser use: it allows us to execute code within the frame and it allows us to send messages between the application and the frame.

Why are these two things so critical? In order for the content shown by the browser to feel fully integrated into the application, the application must have a means to interact with it. These two capabilities are precisely what we need to do this.

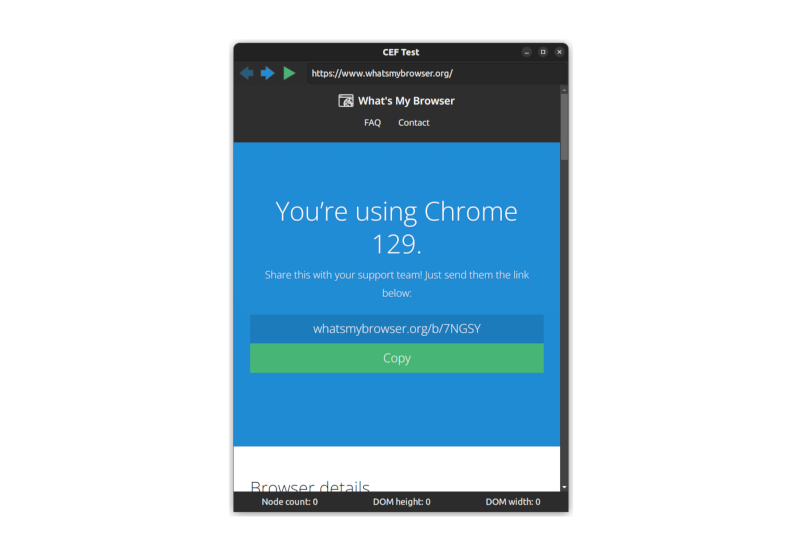

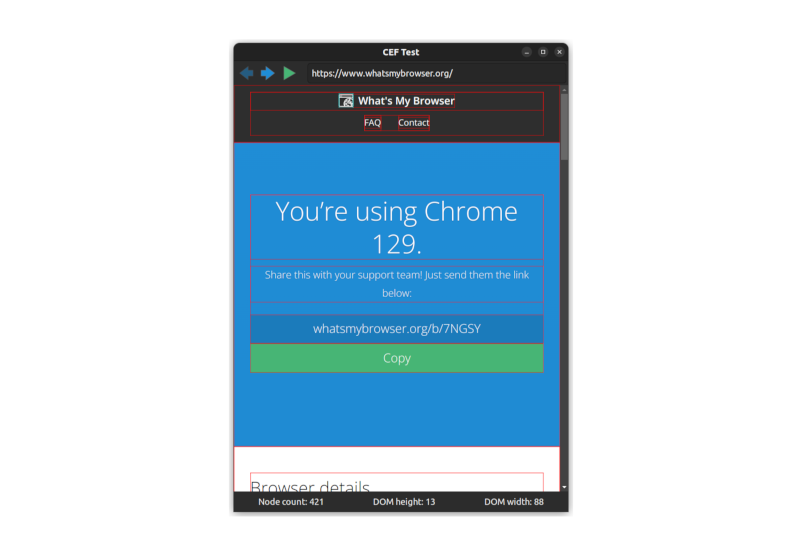

Understanding CEF requires a lot more than these three classes, but this is a supposed to be a survey, not a tutorial. Still, it would be nice to know what it's like to use these classes in practice. To that end, I've put together a simple example CEF application that makes use of some of this functionality.

The application itself is simple and useless, but designed to capture functionality that might be repurposed for better use in other situations. The app displays a single window containing various widgets built using the native toolkit (in the case of our CEF example, these are Gtk widgets). The browser view is embedded between these widgets to demonstrate that it could potentially be embedded anywhere on the page.

The native widgets allow some limited control over the browser content: a URL bar, forwards and backwards. There's also an "execute JavaScript" button. This is the more interesting functionality. When the user presses this a small piece of JavaScript will be executed in the DOM context of the page being rendered.

Here's the JavaScript to be executed:

function collect_node_stats(global_context, local_context, node) {

// Update the context

local_context.depth += 1;

local_context.breadth.push(node.childNodes.length);

global_context.nodes += 1;

global_context.maxdepth = Math.max(local_context.depth,

global_context.maxdepth);

// Recurse into child nodes

for (child of node.childNodes) {

child_context = structuredClone(local_context);

child_context.breadth = local_context.breadth.slice(0, local_context.depth

+ 1);

child_context = collect_node_stats(global_context, child_context, child);

// Recalculate the child breadths

for (let i = local_context.depth + 1; i < child_context.breadth.length;

++i) {

local_context.breadth[i] = (local_context.breadth[i]||0) +

child_context.breadth[i];

}

}

// Paint the DOM red

if (node.style) {

node.style.boxShadow = "inset 0px 0px 1px 0.5px red";

}

// Move back up the tree

local_context.depth -= 1;

return local_context;

}

function node_stats() {

// Data available to all nodes

let global_context = {

"nodes": 0,

"maxdepth": 0,

"maxbreadth": 0

}

// Data that's local to the node and shared with the parent

let local_context = {

"depth": 0,

"breadth": [1]

}

// Off we go

local_context = collect_node_stats(global_context, local_context, document);

global_context.maxbreadth = Math.max.apply(null, local_context.breadth);

return global_context;

}

// Return the results (only strings allowed)

// See: DomWalkHandler::Execute() defined in renderer/client_renderer.cc

dom_walk(JSON.stringify(node_stats()))

I'm including all of it here because it's not too long, but there's no need to go through this line-by-line. All it does is walk the page DOM tree, giving each item in the DOM a red border and collecting some statistics as it goes. As it goes along it collects information that allows us to calculate the number of nodes, the maximum height of the DOM tree and the maximum breadth of the DOM tree.There is one peculiar aspect to this code though: having completed the walk and returned from collect_node_stats() the code then converts the results into a JSON string and passes the result into a function called dom_walk(). But this function doesn't exist. Huh?!

We'll come back to this.

The values that are calculated aren't really important, what is important is that we can return these values at the end and display them in the native user interface code. This highlights not only how an application can have its own code executed in the browser context, but also how the browser can communicate back information to the application. With these, we can make our browser and application feel seamlessly integrated, rather than appear as two different apps that happen to be sharing some screen real-estate.

Let's now delve in to some code and consider how our three classes are being used. We'll then move on to how the communication between app and browser is achieved.

To get the CEF example working I followed the advice in the documentation and made a fork of the cef-project repository. I then downloaded the binary install of the cef project, inside which is an example application called cefclient. I made my own copy of this inside my cef-project fork, hooked it into the CMake build files and started making changes to it.

There's a lot of code there which may look a bit overwhelming but bear in mind that the vast majority of this code is boilerplate taken directly from the example. Writing this all from scratch would have been... time consuming.

Most of the changes I did make were to the file. This handles the browser lifecycle as described above using an instance of the CefBrowserHost class.

We can see this in the RootWindowGtk::CreateRootWindow() method which is responsible for setting up the contents of the main application window. In there you'll see lots of calls for creating and arranging Gtk widgets (I love Gtk, but admittedly it can be a tad verbose). Further down in this same method we see the call to CefBrowserHost::CreateBrowser() that brings the browser component to life.

In the case of CEF the browser isn't actually a component. We tell the browser where in our window to render and it goes ahead and renders, so we actually create an empty widget and then update the browser content bounds every time the size or position of this widget changes.

This contrasts with the Qt WebEngine and Gecko WebView approach, where the embedded browser is provided as an actual widget and, consequently, the bounds are updated automatically as the widget updates. Here with CEF we have to do all this ourselves.

It's not hard to do, and it brings extra control for greater flexibility, but it also hints at why so much boilerplate code is needed.

The browser lives on until the app calls CefBrowserHost::CloseBrowser() in the event that the actual Gtk window containing it is deleted.

We already talked about the native controls in the window and the fact that we can enter a URL, as well as being able to navigate forwards and backwards through the browser history. For this functionality we use the CefBrowser object.

We can see this at work in the same file. Did I mention that this file is where most of the action happens? That's because this is the file that handles the Gtk window and all of the interactions with it.

When creating the window we set up a generic RootWindowGtk::NotifyButtonClicked() callback to handle interactions with the native Gtk widgets. Inside this we find some code to get our CefBrowser instance and call one of the navigation functions on it. The choice of which to call depends on the button that was pressed by the user:

CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> browser = GetBrowser();

if (!browser.get()) {

return;

}

switch (id) {

case IDC_NAV_BACK:

browser->GoBack();

break;

case IDC_NAV_FORWARD:

browser->GoForward();

[...]

Earlier we mentioned that we also have this special execute JavaScript button. I've hooked this up slightly differently, so that it has its own callback for when clicked.The format is similar, but when clicked it extracts the main frame from the browser in the form of a CefFrame instance and calls the CefFrame::ExecuteJavaScript() method on this instead. Like this:

void RootWindowGtk::DomWalkButtonClicked(GtkButton* button,

RootWindowGtk* self) {

CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> browser = self->GetBrowser();

if (browser.get()) {

CefRefPtr<CefFrame> frame = browser->GetMainFrame();

frame->ExecuteJavaScript(self->dom_walk_js_, "", 0);

}

}

The dom_walk_js_ member is just a string buffer containing the contents of our JavaScript file (which I load at app start up). As the method name implies, calling ExecuteJavaScript() will immediately execute the provided JavaScript code in the view's DOM context, starting execution from the line provided.There are similar methods available for the Qt WebEngine and Gecko WebView as well. As we'll see, what makes the CEF version different is that it doesn't block the user interface thread during execution and doesn't return a value. But as we discussed above, we want to return a value, because otherwise how are we going to display the number of nodes, tree height and tree breadth in the user interface?

This is where that mysterious dom_walk() method that I mentioned earlier comes in. We're going to create this method on the C++ side so that when the JavaScript code calls it, it'll execute some C++ code rather than some JavaScript code.

We do this by extending the CefV8Handler class and overriding its CefV8Handler::Execute() method with the following code:

bool DomWalkHandler::Execute(const CefString& name,

CefRefPtr<CefV8Value> object,

const CefV8ValueList& arguments,

CefRefPtr<CefV8Value>& retval,

CefString& exception) {

if (!arguments.empty()) {

// Create the message object.

CefRefPtr<CefProcessMessage> msg = CefProcessMessage::Create(

"dom_walk");

// Retrieve the argument list object.

CefRefPtr<CefListValue> args = msg->GetArgumentList();

// Populate the argument values.

args->SetString(0, arguments[0]->GetStringValue());

// Send the process message to the main frame in the render process.

// Use PID_BROWSER instead when sending a message to the browser process.

browser->GetMainFrame()->SendProcessMessage(PID_BROWSER, msg);

}

return true;

}

This code is going to execute on the render thread, so we still need to get our result to the user interface thread. I say "thread", but it could even be a different process. So this is where the SendProcessMessage() call at the end of this code snippet comes in. The purpose of this is to create a message with a payload made up of the arguments passed in to the dom_walk() method (which, if you'll recall, is a stringified JSON structure). We then send this as a message to the browser process.In JavaScript functions are just like any other value, so to get our new function into the DOM context all we need to do is create a CefV8Value object, which is the C++ name for a JavaScript value, and pass it in to the global context for the browser. We do this when the JavaScript context is created like so:

void OnContextCreated(CefRefPtr<ClientAppRenderer> app,

CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> browser,

CefRefPtr<CefFrame> frame,

CefRefPtr<CefV8Context> context) override {

message_router_->OnContextCreated(browser, frame, context);

if (!dom_walk_handler) {

dom_walk_handler = new DomWalkHandler(browser);

}

CefRefPtr<CefV8Context> v8_context = frame->GetV8Context();

if (v8_context.get() && v8_context->Enter()) {

CefRefPtr<CefV8Value> global = v8_context->GetGlobal();

CefRefPtr<CefV8Value> dom_walk = CefV8Value::CreateFunction(

"dom_walk", dom_walk_handler);

global->SetValue("dom_walk", dom_walk,

V8_PROPERTY_ATTRIBUTE_READONLY);

CefV8ValueList args;

dom_walk->ExecuteFunction(global, args);

v8_context->Exit();

}

}

Finally in our browser thread we set up a message handler to listen for when the dom_walk message is received from the render thread.

if (message_name == "dom_walk") {

if (delegate_) {

delegate_->OnSetDomWalkResult(message->GetArgumentList()->GetString(0));

}

}

Back in our root_window_gtk.cc file is the implementation of OnSetDomWalkResult() which takes the string passed to it, parses it and displays the content in our info bar at the bottom of the window:

void RootWindowGtk::OnSetDomWalkResult(const std::string& result) {

CefRefPtr<CefValue> parsed = CefParseJSON(result,

JSON_PARSER_ALLOW_TRAILING_COMMAS);

int nodes = parsed->GetDictionary()->GetInt("nodes");

int maxdepth = parsed->GetDictionary()->GetInt("maxdepth");

int maxbreadth = parsed->GetDictionary()->GetInt("maxbreadth");

gchar* nodes_str = g_strdup_printf("Node count: %d", nodes);

gtk_label_set_text(GTK_LABEL(count_label_), nodes_str);

g_free(nodes_str);

gchar* maxdepth_str = g_strdup_printf("DOM height: %d", maxdepth);

gtk_label_set_text(GTK_LABEL(height_label_), maxdepth_str);

g_free(maxdepth_str);

gchar* maxbreadth_str = g_strdup_printf("DOM width: %d",

maxbreadth);

gtk_label_set_text(GTK_LABEL(width_label_), maxbreadth_str);

g_free(maxbreadth_str);

}

As you can see, most of this final piece of the puzzle is just calling the Gtk code needed to update the user interface.So now we've gone full circle: the user interface thread executes some JavaScript code on the render thread in the view's DOM context. This then calls a C++ method also on the render thread, which sends a message to the user interface thread, which updates the widgets to show the result.

All of the individual steps make sense in their own way, but it is, if I'm honest, a bit convoluted. I can fully understand that message passing is needed between the different threads, but it would have been nice to be able to send the message directly from the JavaScript. Although there are constraints that apply here for security reasons, the Qt WebEngine and Gecko WebView equivalents both abstract these steps away from the developer, which makes life a lot easier.

With all of this hooked up, pressing the execute JavaScript button now has the desired effect.

The CEF project works hard to make Blink accessible as an embedded browser, but there's still plenty of complexity to contend with. Given just the few pieces we've covered here — lifecycle, navigation, JavaScript execution and message passing — you'll likely be able to do the majority of things you might want with an embedded browser. Crucially, you can integrate the browser component seamlessly with the rest of your application.

It's powerful stuff, but it's also true to say that the other approaches I tried out managed to hide this complexity a little better. The main reason for this would seem to be because CEF doesn't target any particular widget toolkit. It can, in theory, be integrated with any toolkit, whether it be on Linux, Windows or macOS.

While that flexibility comes at a cost in terms of complexity, that hasn't stopped CEF becoming popular. It's widely used by both open source and commercial software, including the Steam client and Spotify desktop app.

In the next section we'll look at the Qt WebEngine, which provides an alternative way to embed the Blink rendering engine into your application.

Qt WebEngine

In the last section we looked at CEF for embedding Blink into an application with minimal restrictions on the choice of GUI framework. We'll follow a similar approach as we investigate Qt WebEngine: first looking at the API, then seeing how we can apply it in practice.Although both uses Blink, there are other important differences between the two. First, Qt WebEngine is tied to Qt. That means that all of the classes we'll look at bar one will inherit from QObject and the main user interface class will inherit from QWidget (which itself is a descendant of QObject).

While Qt is largely written in C++ and targets C++ applications, we'll also make use of QML for our example code. This will make the presentation easier, but in practice we could achieve exactly the same results using pure C++. We'd just end up with a bit more code.

So, with all that in mind, let's get to it.

The fact that Qt WebEngine exclusively targets Qt applications does make things a little simpler, both for the Qt WebEngine implementation and for our use of it. Consequently we can focus on just two classes. In practice there are many more classes that make up the API, but many of these have quite specific uses (such as interacting with items in the navigation history, or handling HTTPS certificates). All useful stuff for sure, but our aim here is just to give a flavour.

The two classes we're going to look at are QWebEnginePage and QWebEngineView. Here's an abridged version of the former:

class QWebEnginePage : public QObject

{

Q_PROPERTY(QUrl requestedUrl...)

Q_PROPERTY(qreal zoomFactor...)

Q_PROPERTY(QString title..)

Q_PROPERTY(QUrl url READ...)

Q_PROPERTY(bool loading...)

[...]

public:

explicit QWebEnginePage(QObject *parent);

virtual void triggerAction(WebAction action, bool checked);

void findText(const QString &subString, FindFlags options,

const std::function<void(const QWebEngineFindTextResult &)>

&resultCallback));

void load(const QUrl &url);

void download(const QUrl &url, const QString &filename);

void runJavaScript(const QString &scriptSource,

const std::function<void(const QVariant &)> &resultCallback);

void fullScreenRequested(QWebEngineFullScreenRequest fullScreenRequest);

[...]

};

If you're not familiar with Qt those Q_PROPERTY macros at the top of the class may be a bit confusing. These introduce scaffolding for setters and getters of a named class variable. The developer still has to define and implement the setter and getter methods in the class. However properties come with a signal method which other methods can connect to. When the value of a property changes, the connected method is called, allowing for immediate reactions to be coded in whenever the property updates.According to the Qt documentation, the QWebEnginePage class...

That's reflected in the methods and member variables I've pulled out here. The title, url and load status of the page are all exposed by this class and it also allows us to search the page. The reference to actions in the documentation relates to the triggerAction() method. There are numerous types of WebAction that can be passed in to this. Things like Forward, Back, Reload, Copy, SavePage and so on.

You'll also notice there's a runJavaScript() method. If you've already read through the section on CEF you should have a pretty good idea about how we're planning to make use of this, but we'll talk in more detail about that later.

The other key class is QWebEngineView. This inherits from QWidget, which means we can actually embed this object in our window. It's the class that actually gets added to the user interface. It's therefore also the route through which we can interact with the QWebEnginePage page object that it holds.

class QWebEngineView : public QWidget

{

Q_PROPERTY(QString title...)

Q_PROPERTY(QUrl url...)

Q_PROPERTY(QString selectedText...)

Q_PROPERTY(bool hasSelection...)

Q_PROPERTY(qreal zoomFactor...)

[...]

public:

explicit QWebEngineView(QWidget *parent);

QWebEnginePage *page() const;

void setPage(QWebEnginePage *page);

void load(const QUrl &url);

void findText(const QString &subString, FindFlags options,

const std::function<void(const QWebEngineFindTextResult &)>

&resultCallback);

QWebEngineSettings *settings() const;

void printToPdf(const QString &filePath, const QPageLayout &layout,

const QPageRanges &ranges);

[...]

public slots:

void stop();

void back();

void forward();

void reload();

[...]

};

Notice the interface includes a setter and getter for the QWebEnginePage object. Some of the page functionality is duplicated (for convenience as far as I can tell). We can also get access to the QWebEngineSettings object through this view, which allows us to configure similar browser settings to those we might find on the settings page of an actual browser.There are also convenience slots for navigation (a slot is just a method that can be either called directly, or connected up to one of the signals I mentioned earlier).

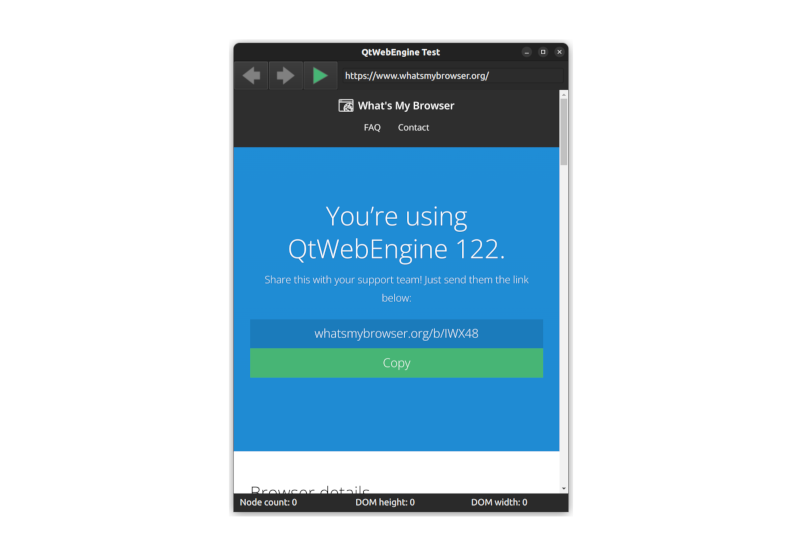

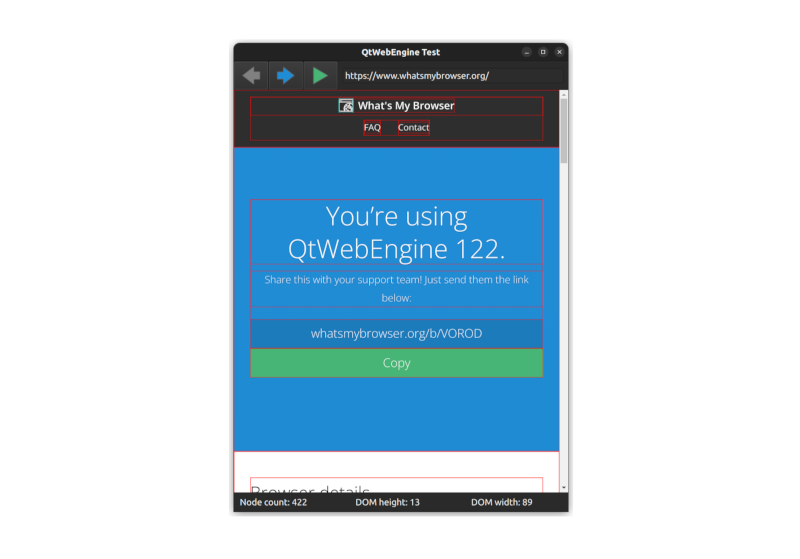

And with these few classes we have what we need to create ourselves an example application. I've created something equivalent to our CEF example application described in the previous section, called WebEngineTest; all of the code for it is available on GitHub, but I'm also going to walk us through the most important parts here.

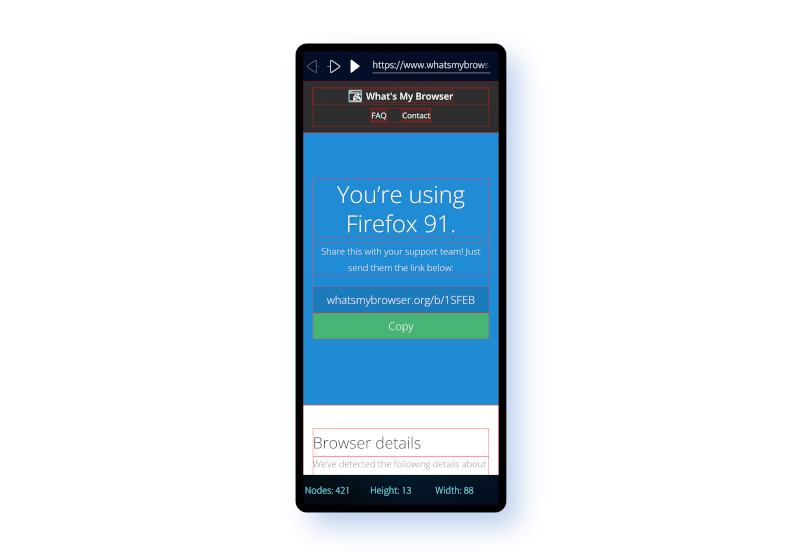

If you looked at the sprawling CEF code, you may be surprised to see how simple the Qt WebEngine equivalent is. The majority of what we need is encapsulated in this short snipped of QML code copied from the Main.qml file.

Column {

anchors.fill: parent

NavBar {

id: toolbar

webview: webview

width: parent.width

}

WebEngineView {

id: webview

width: parent.width

height: parent.height - toolbar.height - infobar.height

url: "https://www.whatsmybrowser.org"

onUrlChanged: toolbar.urltext.text = url

settings.javascriptEnabled: true

function getInfo() {

runJavaScript(domwalk, function(result) {

infobar.dominfo = JSON.parse(result);

});

}

}

InfoBar {

id: infobar

}

}

This column fills the entire application window and essentially makes up the complete user interface for our application. The column contains three rows. At the top and bottom are a NavBar widget and an InfoBar widget respectively. Nestled between the two is a WebEngineView component, which is an instance of the class with the same name that we described above.We'll take a look at the NavBar and InfoBar shortly, but let's first concentrate on the WebEngineView. It has a width set to match the width of the page and a height set to match the page height minus the size of the other widgets. We set the initial page to load and set JavaScript to be enabled, like so:

settings.javascriptEnabled: trueAs it happens JavaScript is enabled by default, so this line is redundant. It's there as a demonstration of how we can interact with the elements inside the QWebEngineSettings component we saw above.

Then there's the getInfo() method that executes the following:

runJavaScript(domwalk, function(result) {

infobar.dominfo = JSON.parse(result);

});

These three lines of code are performing all of the complex message passing steps that we described at length for the CEF example. We call runJavaScript() which is provided by the QML interface as a shortcut to the method from QWebEnginePage.The method takes the JavaScript script to execute — as a string — for its first parameter and a callback that's called on completion of execution for the second parameter. Internally this is actually doing something very similar to the CEF code we saw above: it passes the code to the V8 JavaScript engine to execute inside the DOM, then waits on a message to return with the results of the call.

In our callback we simply copy the returned data into the infobar.dominfo variable, which is used to populate the widgets along the bottom of the screen.

It all looks very clean and simple. But there is some machinery needed in the background to make it all hang together. First, you may have noticed that for our script we simply pass in a domwalk variable. We set this up in the main.cpp file (which is the entrypoint of our application). There you'll see some code that looks like this:

QString domwalk;

QFile file(":/js/DomWalk.js");

if (file.open(QIODevice::ReadOnly)) {

domwalk = file.readAll();

file.close();

}

engine.rootContext()->setContextProperty("domwalk", domwalk);

This is C++ code that simply loads the file from disk, stores it in the domwalk string and then adds the domwalk variable to the QML context. Doing this essentially makes domwalk globally accessible in all the QML code. If we were writing a larger more complex application we might approach this differently, but it's fine here for the purposes of demonstration.Next up, let's take a look at the NavBar.qml file. QML automatically creates a widget named NavBar based on the name of the file, which we saw in use above as part of the main page.

Row {

height: 48

property WebEngineView webview

property alias urltext: urltext

NavButton {

icon.source: "../icons/back.png"

onClicked: webview.goBack()

enabled: webview.canGoBack

}

NavButton {

icon.source: "../icons/forward.png"

onClicked: webview.goForward()

enabled: webview.canGoForward

}

NavButton {

icon.source: "../icons/execute.png"

onClicked: webview.getInfo()

}

Item {

width: 8

height: parent.height

}

TextField {

id: urltext

y: (parent.height - height) / 2

text: webview.url

width: parent.width - (parent.height * 3.6) - 16

color: palette.windowText

onAccepted: webview.url = text

}

}

As we can see, the toolbar is a row of five widgets. Three buttons, a spacer and the URL text field. The first two buttons simply call the goBack() and goForward() methods on our QWebEngineView class. The only other thing of note is that we also enable or disable the buttons based on the status of the canGoBack and canGoForward properties. This is where the signals we discussed earlier come in: when these variables change, they will output signals which are bound to these properties so that the change is propagated throughout the user interface. That's a Qt thing and it works really nicely for user interface development.Finally for the toolbar, the third button simply calls the getInfo() method that we created as part of the definition of our WebEngineView widget above. We already know what this does, but just to recap, this will execute the domwalk JavaScript inside the DOM context and store the result in the infobar.dominfo variable.

The NavButton component type used here is just a simple wrapper around the QML Button QML.

Now let's look at the code in the InfoBar.qml file:

Row {

height: 32

anchors.horizontalCenter: parent.horizontalCenter

property var dominfo: {

"nodes": 0,

"maxdepth": 0,

"maxbreadth": 0

}

InfoText {

text: qsTr("Node count: %1").arg(dominfo.nodes)

}

InfoText {

text: qsTr("DOM height: %1").arg(dominfo.maxdepth)

}

InfoText {

text: qsTr("DOM width: %1").arg(dominfo.maxbreadth)

}

}

The overall structure here is similar: it's a row of widgets, in this case three of them, each a text label. The InfoText component is another simple wrapper, this time around a QML Text widget. As you can see the details shown in each text label are pulled in from the dominfo variable. Recall that when the domwalk JavaScript code completes execution, the callback will store the resulting structure into the dominfo variable we see here. This will cause the nodes, maxdepth and maxbreadth fields to be updated, which will in turn cause the labels to be updated as well.And it works too. Clicking the execute JavaScript button will paint the elements of the page with a red border and display the stats in the infobar, just as happened with our CEF example:

When I first started using QML this automatic updating of the fields felt counter-intuitive. In most programming languages if an expression includes a variable, the value at the point of assignment is used and the expression isn't reevaluated if the variable changes value. In QML if a variable is defined using a colon : (as opposed to an equals =) symbol, it will be bound to the variables in the expression and updated if they change. This is what's happening here: when the dominfo variable is updated, all of its dependent bound variables will be updated too. All made possible using the magical signals from earlier.

Other user interface frameworks (Svelte springs to mind) have this feature as well; when used effectively it can make for super-simple and clean code.

There's just one last piece of the puzzle, which is the domwalk code itself. I'm not going to list it here, because it's practically identical to the code we used for the CEF example, which is listed above. The only difference is the way we return the result back at the end. You can check out the DomWalk.js source file if you'd like to compare.

And that's it. This is far simpler than the code needed for CEF, although admittedly the CEF code all made perfect sense. Unlike CEF, Qt WebEngine is only intended for use with Qt. This fact, combined with the somewhat less verbose syntax of QML compared to C++, is what makes the Qt version so much more concise.

In both cases the underlying Web rendering and JavaScript execution engines are the same: Blink and V8 respectively. It's only the way the Chromium API is exposed that differs.

Let's now move on to the Sailfish WebView, which has a similar interface to Qt WebEngine but uses a different engine in the background.

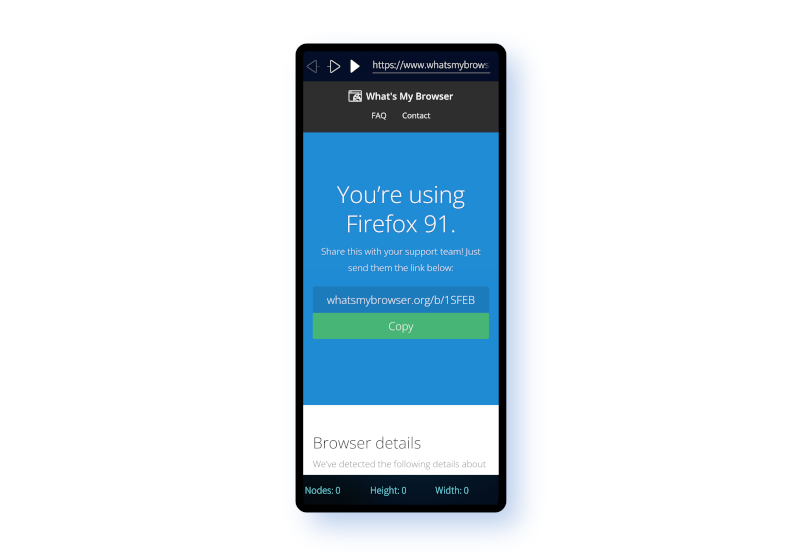

Sailfish WebView

The Sailfish WebView differs from our previous two examples in some important respects. First and foremost it's designed for use on Sailfish OS, a mobile Linux-based operating system. The Sailfish WebView won't run on other Linux distributions, mainly because Sailfish OS uses a bespoke user interface toolkit called Silica, which is built on top of Qt, but which is specifically targeted at mobile use.Although the Sailfish WebView may therefore not be so useful outside of Sailfish OS, it's Sailfish OS that drives my interest in mobile browsers. So from my point of view it's very natural for me to include it here.

Since it's built using Qt and is exposed as a QML widget, the Sailfish WebView has many similarities with Qt WebEngine. In fact the Qt WebEngine API is itself a successor of the Qt WebView API, which was previously available on Sailfish OS and which the Sailfish WebView was developed as a replacement for.

So expect similarities. However there's also one crucial difference between the two: whereas the Qt WebEngine is built using Blink and V8, the Sailfish WebView is built using Gecko and SpiderMonkey. So in the background they're making use of completely different Web rendering engines.

Like the other two examples, all of the code is available on GitHub. The repository structure is a little different, mostly because Sailfish OS has its own build engine that's designed for generating RPM packages. Although the directory structured differs, for the parts that interest us you'll find all of the same source files across both the WebEngineTest and harbour-webviewtest.

Looking first at the Main.qml file there are only a few differences between this and the equivalent file in the WebEngineTest repository.

Column {

anchors.fill: parent

NavBar {

id: toolbar

webview: webview

width: parent.width

}

WebView {

id: webview

width: parent.width

height: parent.height - (2 * Theme.iconSizeLarge)

url: "https://www.whatsmybrowser.org/"

onUrlChanged: toolbar.urltext.text = url

Component.onCompleted: {

WebEngineSettings.javascriptEnabled = true

}

function getInfo() {

runJavaScript(domwalk, function(result) {

infobar.dominfo = JSON.parse(result);

});

}

}

InfoBar {