List items

Items from the current list are shown below.

Blog

24 Jan 2016 : Deconstructing Gone Home #

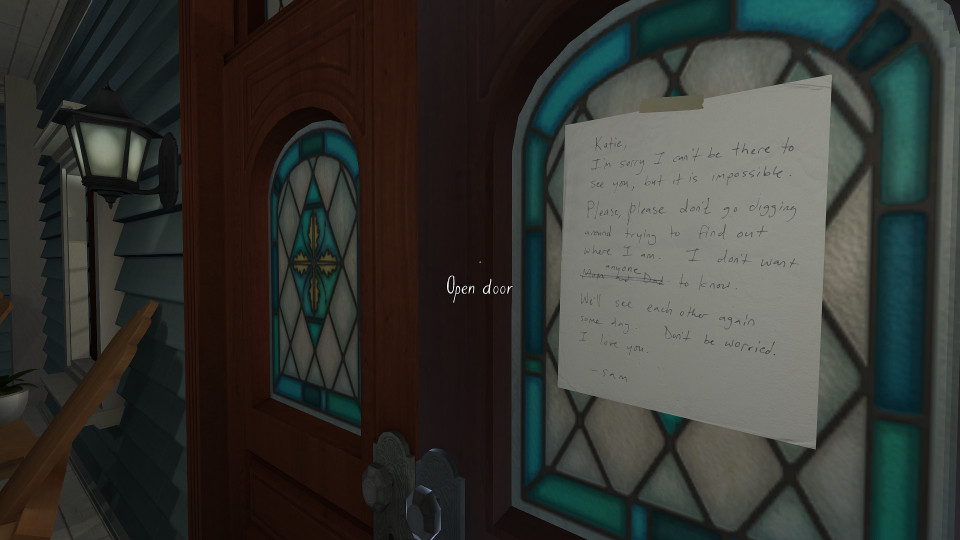

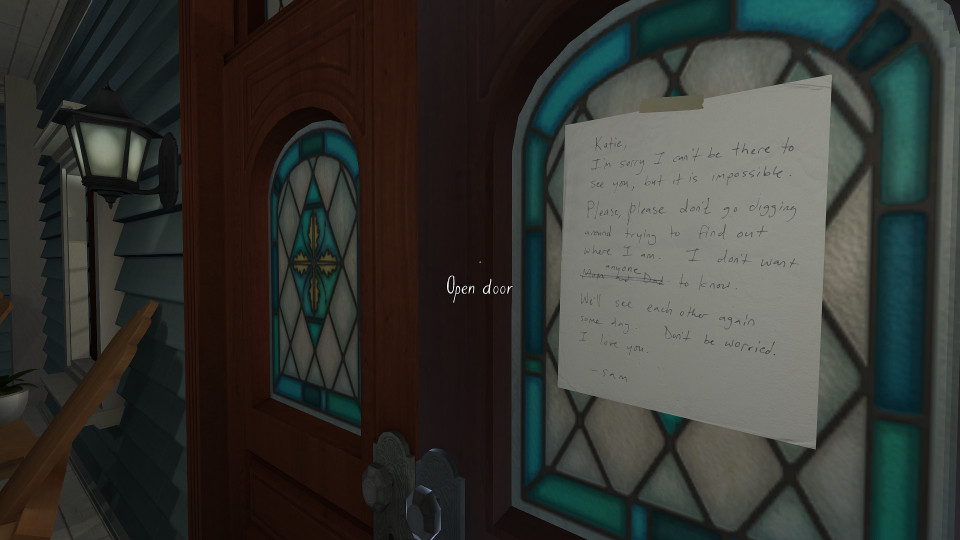

They say that mastery is not a question of specialization, but sureness of purpose and dedication to craft. Gone Home demonstrates that the application of all three can generate wonderful results. While most games revel in their use of varied and multifarious mechanics – singleplayer, multiplayer, cover mechanisms, rewards, dizzying weapon counts and location changes – Gone Home sticks to a single plan with minimal mechanics and delivers it flawlessly.

Everything is driven by the narrative, which takes a layered approach. There’s no choice as such and this isn’t a choose-your-own adventure. In spite of that, a huge amount of trust is bestowed on the player which allows them to miss large portions of the story if they so choose. This trust is rooted in the mechanics of the game rather than the story, and ultimately makes the game far more rewarding.

To understand this better we need to deconstruct the game with a more analytic approach. A good place to start with this is the gameplay mechanics, but it will inevitably require us to consider the story as well. So, here be spoilers. If you’ve not yet played the game, I urge you to do so before reading any further.

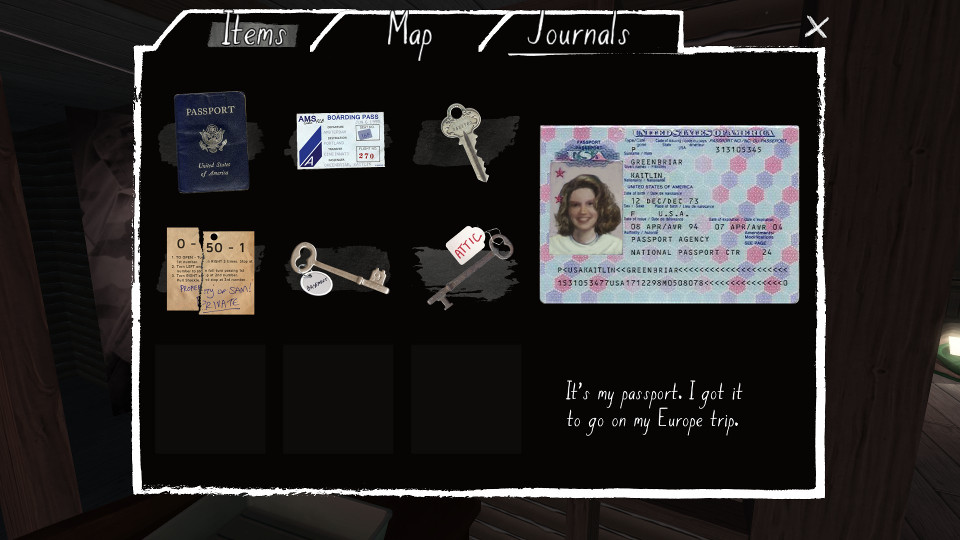

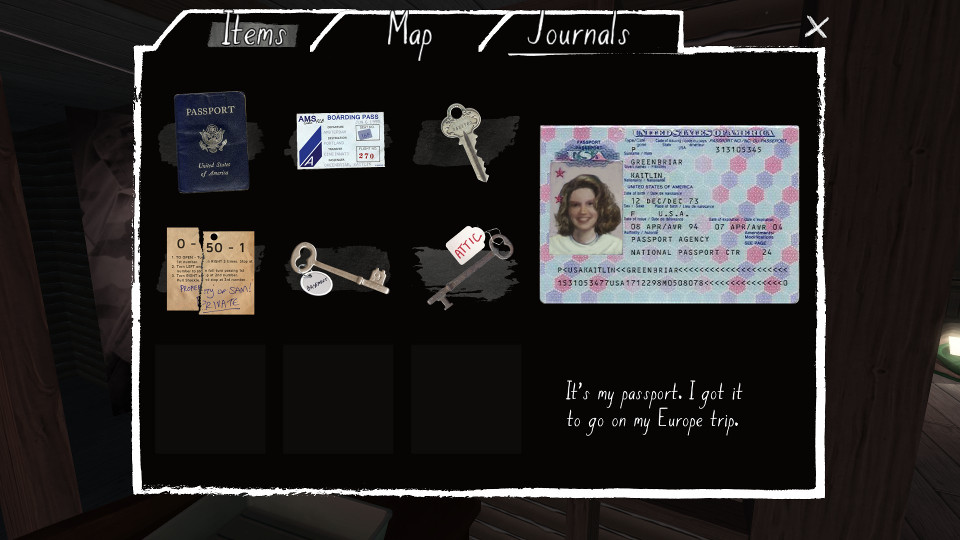

Even though the game is full 3D first-person perspective, the mechanics are pretty sparse. The broad picture is that you have scope to move around the world, pick up and inspect objects, discover ‘keys’ to unlock new areas, and listen to audio diaries. This is a common mechanic used in games and even the use of audiologs has become somewhat of a gaming trope. The widely acclaimed Bioshock franchise uses them as an important (but not the only) narrative device. They’re used similarly in Dead Space, Harley Quinn’s recordings in Batman, the audiographs in Dishonored, and the audio diaries in the rebooted Tomb Raider. Variants include Deus Ex’s email conversations and Skyrim’s many books that provide context for the world. There are surely many others, but while some of these rely heavily on audiologs to maintain their story, few of them use it as a central gameplay mechanic. Bioshock, for example, emphasises fight sequences far more and includes interactions with other characters such as Atlas or Elizabeth for story development. Gone Home provides perhaps the most pure example of the use of audiologs as a central mechanic.

So mechanically this is a pure exploration game. This makes it an ideal game for further analysis, since the depth of mechanics remain tractable. As we’ll see, the mechanics in play actually feel sparser than they are. By delving just a bit into the game we find there’s more going on than we might have imagined on first inspection.

Starting with the interactions, we can categorise theses into eight core ‘active’ mechanics and a further five ‘passive’ types.

Active interaction types

While the key mechanism for driving the narrative forward is exploration through inspecting objects, it’s perhaps more enlightening to first understand the mechanisms used to restrict progress. All games must balance player agency against narrative cohesion. If the player skips too far forward they may miss information that’s essential for understanding the story. If the player is forced carefully along a particular route the sense of agency is lost, and can also lead to frustration if progress is hindered unnecessarily. Sitting in between is a middle ground that trusts the player to engage with the game and relies on them to manage and reconstruct information that may be presented out-of-order, incomplete and in multiple ways.

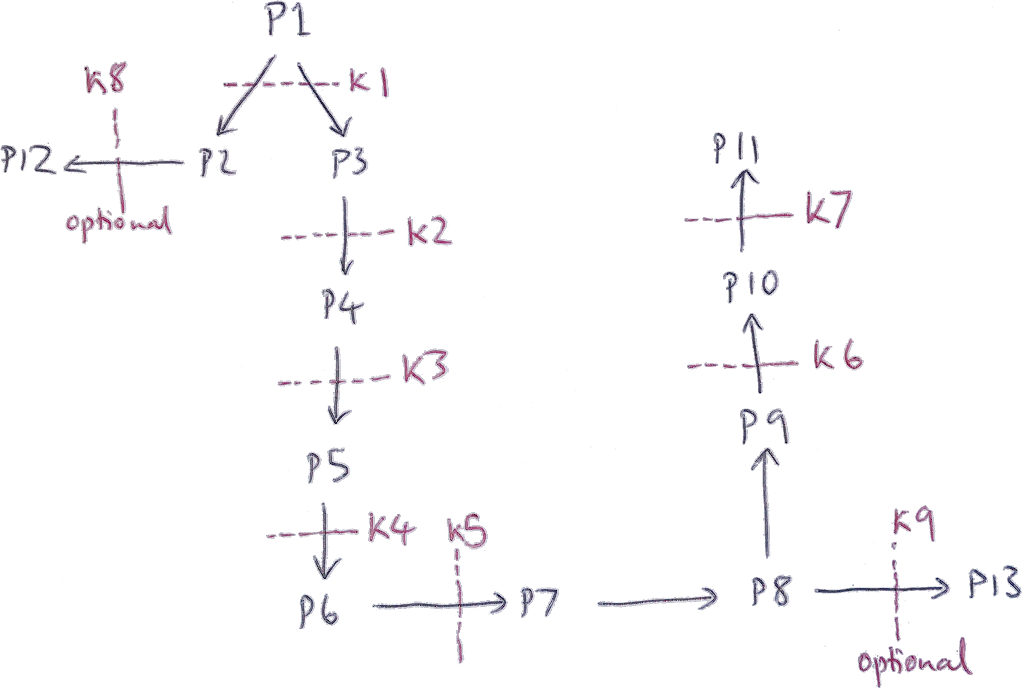

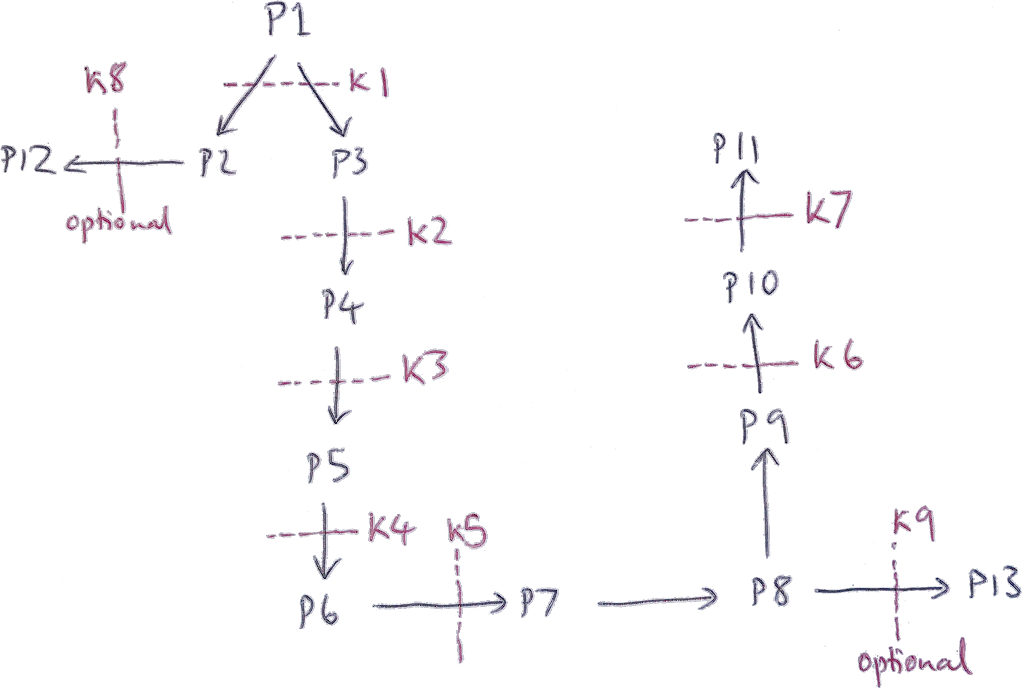

There are then seven main ‘bulkheads’ (K1-K7) that define eight areas that force the narrative to follow a given sequence. On top of this there are two optional ‘sidequest bulkheads’ (K8, K9). The map itself can be split into twelve areas, and the additional breakpoints help direct the flow of the player, although where no keys are indicated this occurs through psychological coercion rather than compulsion.

These areas shown in the diagram are as follows.

Given there are twenty five audio diaries, and a huge number of other written items and objects which add to the story, it’s clear that The Fullbright Company (the Gone Home developers) assume a reasonable amount of flexibility in the ordering of the information within these eight areas. It’s very easy to miss a selection of them on a single run-through of the game.

The diaries themselves only capture the main narrative arc – Sam’s coming-of-age – which interacts surprisingly loosely with the other arcs that can be found. These can be most easily understood by categorising them in terms of characters:

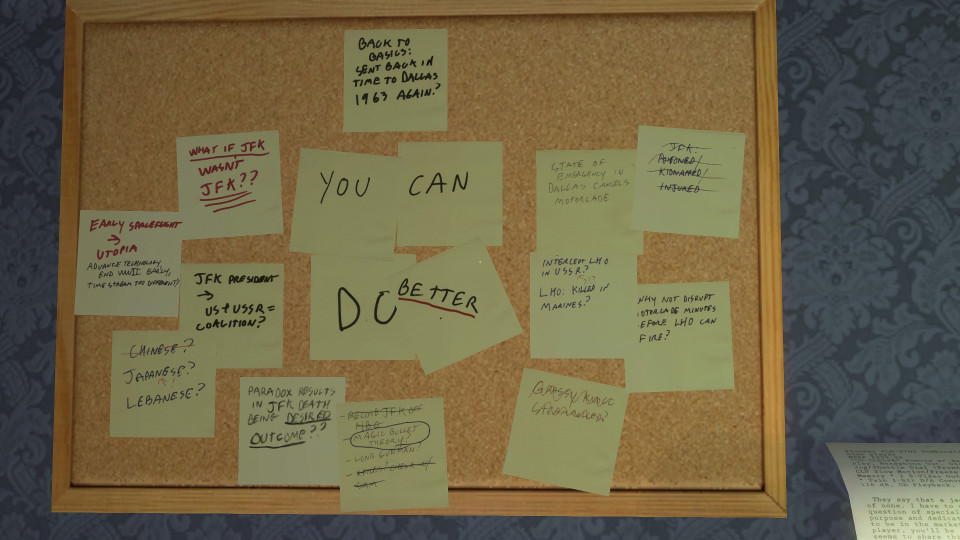

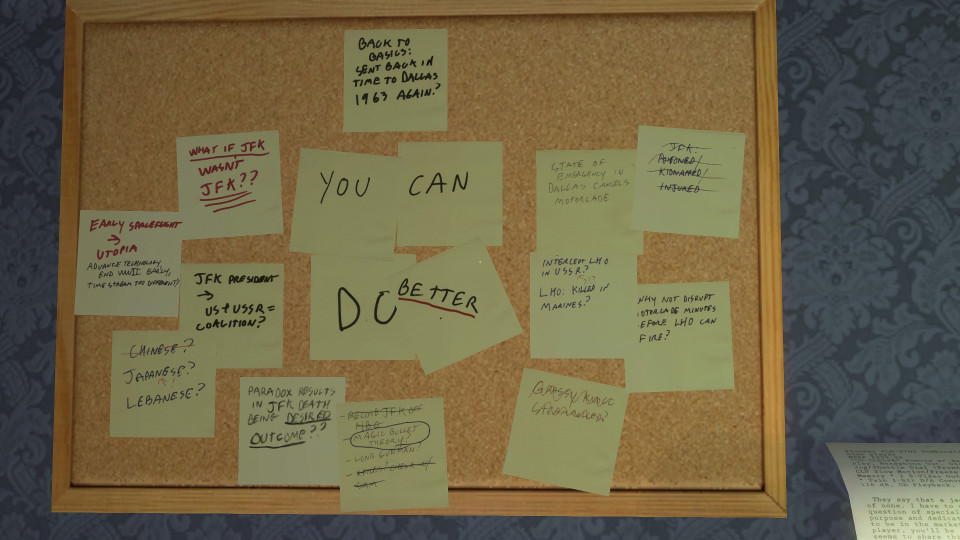

An interesting feature of these stories is that they each conform to different literary genres, and this helps to obscure the nature of the story, allowing the ending to remain a surprise up until the last diary entry. Terrance’s career has elements of tragedy which are reinforced by the counterbalancing romance of Jan’s affair. Oscar’s story, which is inseparable from that of the house itself, introduces elements of horror. Kaitlin’s story is the least developed, but is perhaps seen best as a detective story driven by the player. Even though you act through Kaitlin as the protagonist, it’s clearly Sam who’s star of the show. Even though it’s clear from early on that the main narrative, seen through Sam’s eyes, is a coming-of-age story, the ending that defines the overall mood (love story, tragedy?) is left open until the very end.

Perhaps another interesting feature is the interplay between the genres and the mechanics. The feel of the game, with bleak weather, temperamental lighting, darkened rooms and careful exploration, is one of survival horror. Initially it seems like the game might fall into this category, with Oscar’s dubious past and the depressed air. This remains a recurrent theme throughout. But ultimately this is used more to provide a backdrop to Sam’s story, transporting Kaitlin through her (your) present-day experiences to those of Sam as described through her audio diaries and writings.

Ultimately then, it’s possible to deconstruct Gone Home into its thirteen main interaction types, eight areas and five narrative arcs. This provides the layering for a rich story and involving game, even though, compared to many of its contemporaries in the gaming arena, it’s mechanically rather limited. By delving into it I was hoping it might provide some insight into how the reverse can take place: the construction of a game based on a fixed set of mechanics and restricted world. It goes without saying that the impact of the story comes from its content and believability, along with pitching the trust balance in the right spot. Neither of these can be captured in an easily reproducible form.

Nonetheless it would be really neat if it were possible to derive a formal approach from this for simplifying the process of creating new material that follows a similar layered narrative approach. Unlike many games Gone Home is complex enough to be enjoyable but simple enough to understand as a whole. It was certainly one of my favourite games of 2014, and if there's a formula for getting such things right, it's a game that's worth replicating.

Addendum: I wrote this back in July 2014 while lecturing on the Computer Games Development course at Liverpool John Moores Univrsity and recently rediscovered it languishing on my hard drive. At the time I thought it might be of interest to my students and planned to develop it into a proper theory. Since I never got around to doing so, and now probably never will, I felt I may as well publish it in its present form.

Everything is driven by the narrative, which takes a layered approach. There’s no choice as such and this isn’t a choose-your-own adventure. In spite of that, a huge amount of trust is bestowed on the player which allows them to miss large portions of the story if they so choose. This trust is rooted in the mechanics of the game rather than the story, and ultimately makes the game far more rewarding.

To understand this better we need to deconstruct the game with a more analytic approach. A good place to start with this is the gameplay mechanics, but it will inevitably require us to consider the story as well. So, here be spoilers. If you’ve not yet played the game, I urge you to do so before reading any further.

Even though the game is full 3D first-person perspective, the mechanics are pretty sparse. The broad picture is that you have scope to move around the world, pick up and inspect objects, discover ‘keys’ to unlock new areas, and listen to audio diaries. This is a common mechanic used in games and even the use of audiologs has become somewhat of a gaming trope. The widely acclaimed Bioshock franchise uses them as an important (but not the only) narrative device. They’re used similarly in Dead Space, Harley Quinn’s recordings in Batman, the audiographs in Dishonored, and the audio diaries in the rebooted Tomb Raider. Variants include Deus Ex’s email conversations and Skyrim’s many books that provide context for the world. There are surely many others, but while some of these rely heavily on audiologs to maintain their story, few of them use it as a central gameplay mechanic. Bioshock, for example, emphasises fight sequences far more and includes interactions with other characters such as Atlas or Elizabeth for story development. Gone Home provides perhaps the most pure example of the use of audiologs as a central mechanic.

So mechanically this is a pure exploration game. This makes it an ideal game for further analysis, since the depth of mechanics remain tractable. As we’ll see, the mechanics in play actually feel sparser than they are. By delving just a bit into the game we find there’s more going on than we might have imagined on first inspection.

Starting with the interactions, we can categorise theses into eight core ‘active’ mechanics and a further five ‘passive’ types.

Active interaction types

- Movement and crouching/zooming

- Picking up objects

- Full rotation

- Lateral rotation

- Reading (possibly with multiple pages)

- Adding an object to your backpack

- Triggering a journal entry

- Playing an audio cassette

- Return object to the same place

- Throw object

- Turn on/off an object (e.g. light, fan, record player, TV)

- Open/close door (including some with locks or one-way entry)

- Open/close cupboards/drawers

- Lock combinations

- Hover text

- Reading object

- Finding clues in elusive hard-to-see places

- Viewing places ahead-of-time (e.g. conservatory)

- Magic eye pictures

While the key mechanism for driving the narrative forward is exploration through inspecting objects, it’s perhaps more enlightening to first understand the mechanisms used to restrict progress. All games must balance player agency against narrative cohesion. If the player skips too far forward they may miss information that’s essential for understanding the story. If the player is forced carefully along a particular route the sense of agency is lost, and can also lead to frustration if progress is hindered unnecessarily. Sitting in between is a middle ground that trusts the player to engage with the game and relies on them to manage and reconstruct information that may be presented out-of-order, incomplete and in multiple ways.

There are then seven main ‘bulkheads’ (K1-K7) that define eight areas that force the narrative to follow a given sequence. On top of this there are two optional ‘sidequest bulkheads’ (K8, K9). The map itself can be split into twelve areas, and the additional breakpoints help direct the flow of the player, although where no keys are indicated this occurs through psychological coercion rather than compulsion.

These areas shown in the diagram are as follows.

- P1. Porch

- P2. Ground floor west

- P3. Upstairs

- P4. Stairs between upstairs and library

- P5. Three secret panels

- P6. Locker

- P7. Basement

- P8. Stairs between basement, guestroom and ground floor east

- P9. Ground floor east

- P10. Room under the stairs

- P11. Attic

- P12. Filing cabinet (optional)

- P13. Safe (optional)

- K1. Christmas duck key

- K2. Sewing room map

- K3. Secret panel map

- K4. Locker combination

- K5. Basement key

- K6. Map to room under stairs in conservatory

- K7. Attic key

- K8. Safe combination in library (optional)

- K9. Note in guestroom (optional)

Given there are twenty five audio diaries, and a huge number of other written items and objects which add to the story, it’s clear that The Fullbright Company (the Gone Home developers) assume a reasonable amount of flexibility in the ordering of the information within these eight areas. It’s very easy to miss a selection of them on a single run-through of the game.

The diaries themselves only capture the main narrative arc – Sam’s coming-of-age – which interacts surprisingly loosely with the other arcs that can be found. These can be most easily understood by categorising them in terms of characters:

- Sam’s coming-of-age (sister)

- Terrance’s literary career (Dad)

- Jan’s affair (Mum)

- Oscar’s life (great uncle)

- Kaitlin’s travel (protagonist)

An interesting feature of these stories is that they each conform to different literary genres, and this helps to obscure the nature of the story, allowing the ending to remain a surprise up until the last diary entry. Terrance’s career has elements of tragedy which are reinforced by the counterbalancing romance of Jan’s affair. Oscar’s story, which is inseparable from that of the house itself, introduces elements of horror. Kaitlin’s story is the least developed, but is perhaps seen best as a detective story driven by the player. Even though you act through Kaitlin as the protagonist, it’s clearly Sam who’s star of the show. Even though it’s clear from early on that the main narrative, seen through Sam’s eyes, is a coming-of-age story, the ending that defines the overall mood (love story, tragedy?) is left open until the very end.

Perhaps another interesting feature is the interplay between the genres and the mechanics. The feel of the game, with bleak weather, temperamental lighting, darkened rooms and careful exploration, is one of survival horror. Initially it seems like the game might fall into this category, with Oscar’s dubious past and the depressed air. This remains a recurrent theme throughout. But ultimately this is used more to provide a backdrop to Sam’s story, transporting Kaitlin through her (your) present-day experiences to those of Sam as described through her audio diaries and writings.

Ultimately then, it’s possible to deconstruct Gone Home into its thirteen main interaction types, eight areas and five narrative arcs. This provides the layering for a rich story and involving game, even though, compared to many of its contemporaries in the gaming arena, it’s mechanically rather limited. By delving into it I was hoping it might provide some insight into how the reverse can take place: the construction of a game based on a fixed set of mechanics and restricted world. It goes without saying that the impact of the story comes from its content and believability, along with pitching the trust balance in the right spot. Neither of these can be captured in an easily reproducible form.

Nonetheless it would be really neat if it were possible to derive a formal approach from this for simplifying the process of creating new material that follows a similar layered narrative approach. Unlike many games Gone Home is complex enough to be enjoyable but simple enough to understand as a whole. It was certainly one of my favourite games of 2014, and if there's a formula for getting such things right, it's a game that's worth replicating.

Addendum: I wrote this back in July 2014 while lecturing on the Computer Games Development course at Liverpool John Moores Univrsity and recently rediscovered it languishing on my hard drive. At the time I thought it might be of interest to my students and planned to develop it into a proper theory. Since I never got around to doing so, and now probably never will, I felt I may as well publish it in its present form.